This article was originally published in December 2021 Medical Writing | Volume 30 Number 4.

Eighteen months before the COVID-19 pandemic began, I wrote about vaccine hesitancy for the March 2018 issue of Medical Writing.

Back then, health communicators were concerned about hesitancy and the MMR vaccine.

We were furious at Andrew Wakefield and frustrated with mothers who spread misinformation online while choosing not to vaccinate their newborns.

How the world has changed.

COVID-19 and hesitancy

As outbreaks and infection rates continue to soar, vaccination – while not a silver bullet – is the only weapon we have against COVID-19. But poor messaging has hindered rollouts and uptake in countries like Australia. For example: our over-60s have had access to vaccines since March – but rates remained low for months. Why? Access issues aside, there are two likely reasons: mixed messaging and a lack of communication specifically addressing hesitations – both of which have created a perfect storm of hesitancy.

In Queensland, where I live, health experts told under-60s not to get the AstraZeneca vaccine[1] due to concern about blood clot risks. In other states, experts encouraged under-60s to get whatever vaccine they could access. Months later, Queensland’s message changed;[2] under-60s could get AstraZeneca if they first spoke to their doctor. Critically, health experts did not specifically address their earlier comments and why they changed their message, creating even more public confusion.

Consistent public health messaging is the key to alleviating fears. Reliable communications that address hesitancy will help to avoid mixed messaging around safety. Messaging needs to be strong enough to motivate behaviour change, too. One of our first consistent public health messages was to get vaccinated to do the right thing and protect your community,[3] but it has since changed to focus more on ‘returning to normal’.

This perfect storm of hesitancy is, of course, worsened by media fearmongering. Journalists love to spread fear through speculation, sensationalist headlines, and language use. But fear doesn’t change behaviours – it creates confusion, which makes hesitancy worse. And, to recap my 2018 piece: knowledge, facts, and evidence alone don’t help to address vaccine hesitancy any more than fear does, unfortunately.

The first step towards addressing hesitancy is putting yourself in your audience’s shoes. Demonstrate an understanding of the hesitation, and then form an effective response.

Putting yourself in your reader’s shoes

Targeted communication is more effective than generic communication. Putting yourself in your reader’s shoes and thinking about what they need to know helps you to communicate clearly, giving you a better chance of achieving your desired result. Asking questions that explore people’s reasoning behind their decisions is a useful first step.

I recently asked my Instagram followers why they got the vaccine, and one astute reader responded with a simple question: Why wouldn’t you? The answer requires a big-picture approach. Why do people do things that are bad for them, and why don’t they do things that are good for them?

It’s not down to stupidity or ignorance, writes emergency physician, Dr Edwin Leap, for MedPage Today.[4] “Human decisions are far more complex, nuanced, and personal than most of us realise.” He added, “We needn’t agree with a choice to understand it,” before offering a few logical reasons why people don’t do things that are good for them, including:

- science is hard to understand

- an understanding of science is not innate

- people distrust pharma companies and the government in general

- poverty

But importantly, not all people who are hesitating feel and think the same. Vaccine hesitancy is a complex spectrum,[5] from consideration right through to outright denial.

Different stages require different messages, and each fear requires a targeted, consistent response. If a hesitant reader reads a different answer every time they express their specific hesitation, they’ll likely feel more confused and hesitant.

Over the past months, I’ve read many perspectives online to understand more about the spectrum of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy. Two of the main themes underlying hesitancy seem to be:

- Fear of the unknown – fears related to long-term side effects, unfamiliar ingredients, and pregnancy risks

- Loss of control over choice – fears related to loss of ownership over one’s body, which also relates to losing control of freedom

Anger and frustration, two highly emotional states, are closely related to these themes. So, it’s not surprising that many of us end up in arguments when discussing hesitancy. Putting yourself in your reader’s shoes helps you avoid arguments, communicate clearly, and engage in respectful debate.

When I asked a friend about her reasons for hesitation, she was more than happy to discuss her feelings rationally. It was like I was the only person who had taken the time to have a civil discussion about hesitation with her. And by understanding and acknowledging her perspective, I was able to learn more about hesitation.

“Treat [people who are hesitant] as potential allies rather than enemies,” concludes Dr Leap. “Try to learn from them and apply that information to future situations. But do not, under any circumstance, treat them as simpletons or dismiss their concerns out of hand.”

Understanding the reasons for hesitation helps you form an effective, relevant response.

Forming an effective response

An effective response should be targeted, evidence-based, and considerate. And we can look to other public health campaigns to see which communication tactics have successfully changed people’s behaviours. For example, health communication research[6] has shown that, while fear alone doesn’t change behaviours, messages of fear combined with messages of hope help to inspire behaviour change.

This effect worked well in a 2017 skin cancer prevention public health campaign. Therefore, a consistent fear-hope vaccination message could work well – as long as it’s not too menacing. Comparably, research into smoking prevention[7] has shown that “short and sweet” messages focused on immediate gains work better than highly threatening or fear-eliciting messages.

A separate study[8] found that negative messages containing deception and disgust pushed readers into defensive responses – making them best avoided. Narratives and real-life success stories are persuasive tools, too. Embedding facts in a story is more persuasive[9] than simply presenting facts alone. Incorporating stories about hesitant individuals who have changed their minds may work well.

Engaging particular groups through targeted communication is important as well. Speaking to News GP,[10] Associate Professor Holly Seale, an infectious disease social scientist also at the UNSW’s School of Population Health, said: “By being activated, by being primed, the research shows people are more likely to go into see their GP and their health provider with a more positive mind frame.”

The final word

If you’re communicating about vaccine hesitancy and you want to discuss the benefits of vaccination, here are the key points to keep in mind:

- Put yourself in your reader’s shoes – understand your reader’s reasons for hesitation

- Form an effective, evidence-based response – use health communication tactics, such as:

- Fear-hope messages (but avoid frightening messages)

- Short and sweet messages focused on immediate gains

- Narratives and real-life success stories to persuade

- Keep your communication targeted – use relevant messages in susceptible communities or age groups.

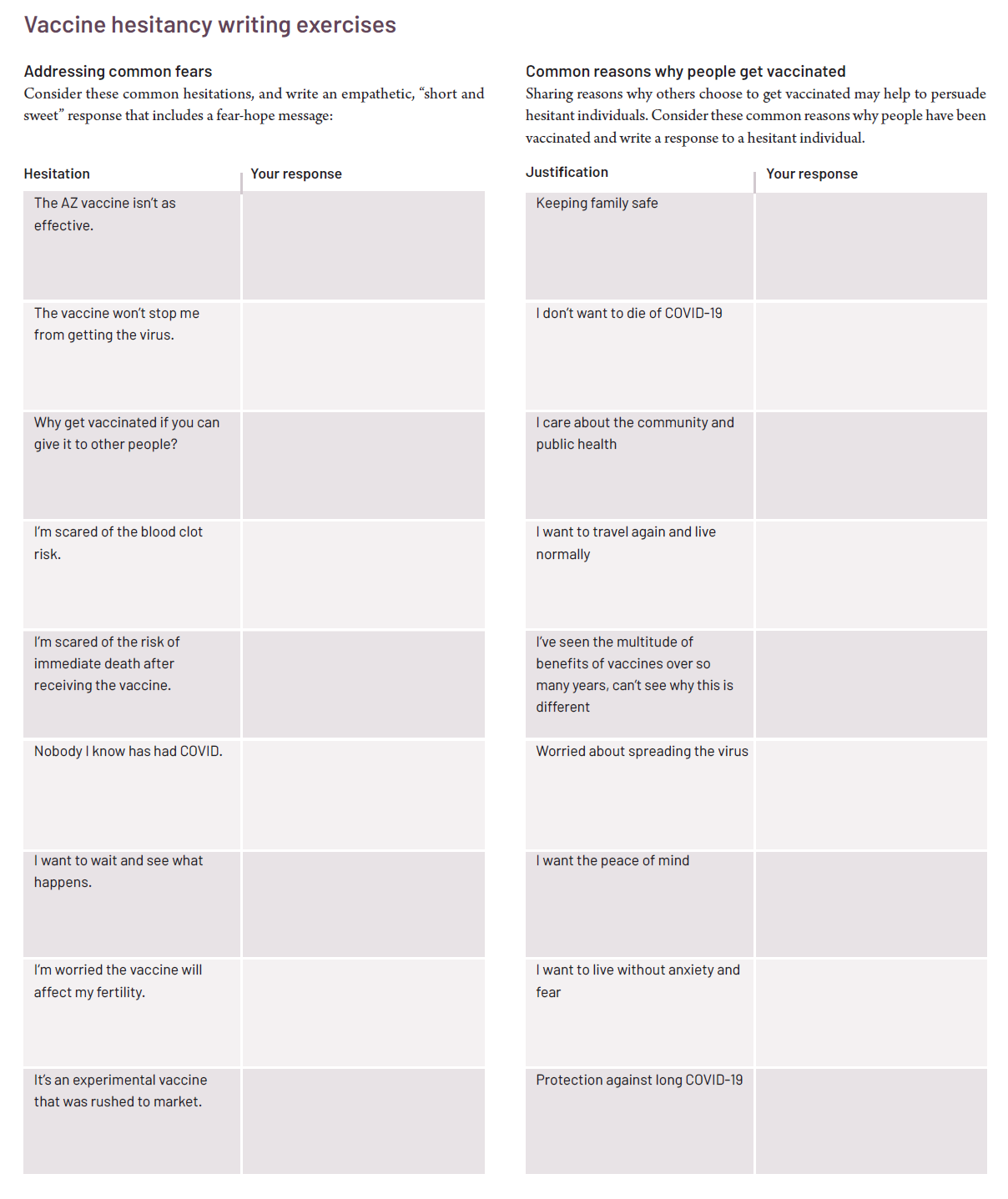

Writing exercises

References

1.Zillman S. Queensland’s Chief Health Officer rejects Prime Minister’s comments on AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine for under-40s. ABC News. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.abc.net.au/news/2021-06-30/qld-cho-rejects-morrisons-astrazeneca-comments-covid-vaccine/100256022

2.Layt S, Dennien M. Queensland CHO modifies AstraZeneca advice as case numbers rise. Brisbane Times. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/ national/queensland/queensland-cho-modifies-astrazeneca-advice-as-case-numbers-rise-20210803-p58fdz.html

3.Why should I get vaccinated for COVID-19? Health.gov.au. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/covid-19-vaccines/getting-vaccinated-for-covid-19/why-should-i-get- vaccinated-for-covid-19

4.Leap E. Vaccine hesitancy is complex. MedPage Today. 2021 July 28; [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www.medpagetoday.com/opinion/ rural/93783

5.Leask J, Danchin M, Chad NJ. Australians’ attitudes to vaccination are more complex than a simple ‘pro’ or ‘anti’ label. The Conversation. 2017 [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://theconversation.com/australians-attitudes-to-vaccination-are-more-complex-than-a-simple-pro-or-anti-label-74245

6.Nabi R, Myrick J. Uplifting fear appeals: Considering the role of hope in fear-based persuasive messages. Health Commun. 2019;34(4):463–74. doi:10.1080/10410236.2017.1422847

7.Mollen S, Engelen S, Kessels LT, van den Putte B. Short and sweet: The persuasive effects of message framing and temporal context in antismoking warning labels. J Health Commun. 2017;22(1):20–28. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1247484

8.Leshner G, Clayton RB, Bolls PD, Bhandari M. Deceived, disgusted, and defensive: Motivated processing of anti-tobacco advertisements. Health Commun. 2018;33(10):1223–32. doi:10.1080/10410236.2017.1350908

9.Krause RJ, Rucker DD. Strategic storytelling: When narratives help versus hurt the persuasive power of facts. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2020;46(2):216–27. doi:10.1177/0146167219853845

10.Attwooll J. Is there enough public data on COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy? NewsGP, RACGP. 2021 [cited 2021 Sep 1]. Available from: https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/is-there-enough-public-data-on-covid-19-vaccine-he